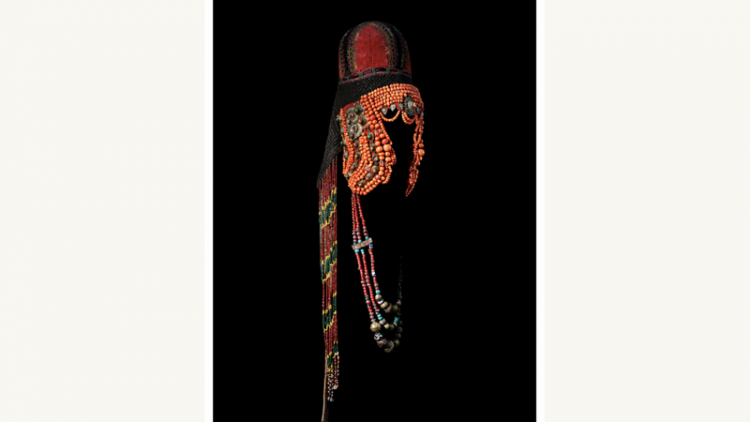

With significant support from the Art and Culture Development Foundation under the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Uzbekistan, visitors will be able to discover around 300 unique pieces that represent remarkable treasures of Uzbekistan: sumptuous chapans (coats) and gold-embroidered accessories from the Emir’s court; hand painted wooden saddles; silver horse harnesses set with turquoise; magnificent suzanis (embroidered hangings); rugs; silk ikats; jewelry, and costumes from nomadic tribes, as well as 40 avant-garde Orientalist paintings.

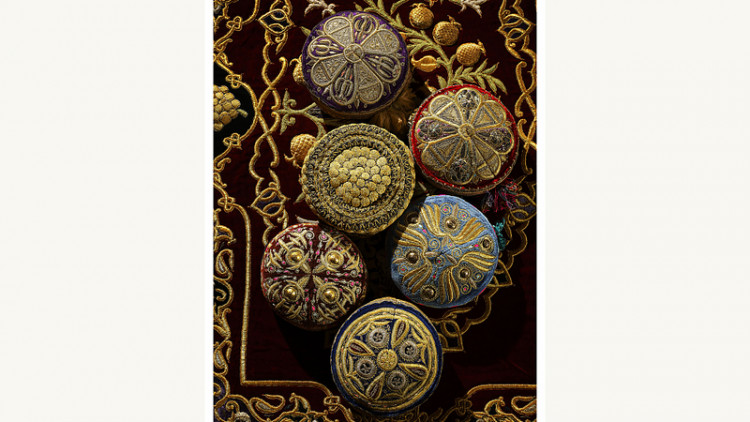

The exhibition showcases the renaissance of artisanal splendors of the 19th and early 20th centuries – being essential components of Uzbek identity. Textiles play an important role in the Islamic world: they distinguish, honor, and convey a strong image in society. Bukhara embroidery in particular has always held a special place amongst many other art forms in the country. It was during the reign of the first Emir of Bukhara, Shah Murad (1860-1885), that gold embroidery reached its peak – renowned for its technique, quality, and above all, creativity. A large number of splendid and monumental productions – chapans, dresses, headdresses, and saddle cloths – combining colors and gold, reserved for the court and used as diplomatic gifts, were crafted exclusively in the Emir’s private workshop, and bore witness to his opulent lifestyle.

The colors and the aesthetic of these creations prove to be a source of inspiration for many visual artists. At the turn of the century, Turkestan was favored by the Russian avant-garde at its zenith between 1917 and 1932. When the Russian Empire disappeared to become the USSR, many Soviet artists rediscovered this territory, the current-day Republic of Uzbekistan. At the same time as Matisse’s encounter with Morocco, the painters of the Russian School found great inspiration in the rich landscapes, shapes, colors, and peoples of Central Asia. In their work, each artist approached this “quest for exoticism” with the guidance of their respective Symbolist, Neo-Primitivist, Constructivist schools, to name a few. In turn, this saw the birth of the Uzbek School, introduced and led by the artist Alexander Volkov. The unique paintings conserved in Nukus are part of the world’s second largest collection of Russian avant-garde art after Saint Petersburg. This collection, presented for the first time in France, was carefully gathered by collector Igor Savitsky. Thanks to his attempts to preserve non-official art threatened by the Soviet authorities in the 1950s, coupled with the attention he gave to the preservation of local history, this remarkable, albeit little-known Russian Orientalist collection can now be showcased across the world.

Situated in the heart of Central Asia, with a landscape of mountains, deserts, fertile plains, and oases, Uzbekistan boasts a rich history and culture. An independent republic since 1991, following the collapse of the USSR, Uzbekistan is the heir to a myriad of ancestral cultures and traditions. A crossroads of civilizations between the peoples of the steppes, India, Persia, China, and the Arab-Muslim world, Uzbekistan was the repository of powerful kingdoms and empires thanks to its unique and strategic political and cultural position. Zoroastrian, Manichean, Buddhist, Jewish, Christian, and Muslim practices have long coexisted here, having a lasting influence on the symbolism and artisanal techniques of the region.

The exhibition is organized by the Arab World Institute and the Art and Culture Development Foundation under the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Uzbekistan (ACDF). The Foundation fosters international cooperation and promotes the culture of Uzbekistan on the international stage. Throughout its existence, ACDF has been working consistently to bring changes to national legislation – something that has made this project possible.